My PD Story

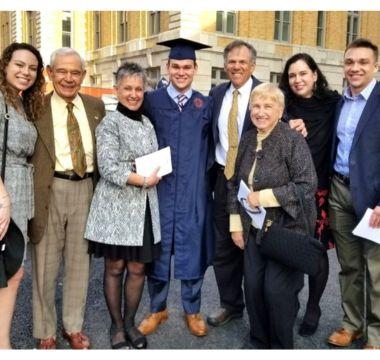

Gustavo A. Suarez Zambrano

Mind the Gap: Bridging the Therapeutic Landscape

Gustavo A. Suarez Zambrano, MD, Vice President of Medical Affairs at Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America, Inc.

Growing up in Colombia, Gustavo A. Suarez Zambrano, MD, always knew he wanted a career where he could help people – though he didn’t know his path would eventually lead to studying Parkinson’s disease (PD) in the U.S.

Dr. Suarez worked for several years as a general physician in hospitals across South America before finding his true passion in neurology. Then, after working for four years as a general neurologist, he realized he wanted to become more specialized. This prompted his move to the U.S., where he secured an opportunity at Baylor College of Medicine, a Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, to study and support research in multiple sclerosis (MS).

After several years in the MS space, Dr. Suarez decided to take on a new challenge. He joined Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America (MTPA) with the goal of getting involved in movement disorders and PD, areas where treatment options are still quite limited.

Right now, many people living with PD experience a decline in efficacy of oral standard of care medication as their disease advances. This requires them to take multiple doses throughout the day to try to control their symptoms, which can often lead to the occurrence of uncontrolled motor fluctuations such as involuntary movements or dyskinesia.

Providing therapeutic options that can positively impact people with PD, especially those impacted by motor fluctuations, is an area of high unmet need. Dr. Suarez’s work at MTPA focuses on trying to address this gap. He understands the critical need for minimally invasive treatment options that could help address these symptoms.

In addition to supporting research and discovery into new treatment options to meet the existing therapeutic needs, Dr. Suarez is also passionate about bridging the education gap to support people with PD, caregivers and healthcare providers in understanding new data and advancements in the field. Therapeutic options are only useful if those living with the disease and those treating the disease are informed and receptive to them.

After many years in neurology, Dr. Suarez now spends a significant amount of his time trying to find new ways to tackle the unmet needs and challenges of Parkinson’s disease, including motor fluctuations, and is committed to continue exploring treatment options for people living with this disease.

For more information on PD and understanding motor fluctuations, visit SpeakParkinsons.com.

Related Materials

Pain in Parkinson's Disease

Occupational Therapy and PD

Managing "Off" Time in Parkinson's

More Stories

from the Parkinson's community