Mental Wellness: Addressing Thinking Changes in Parkinson's

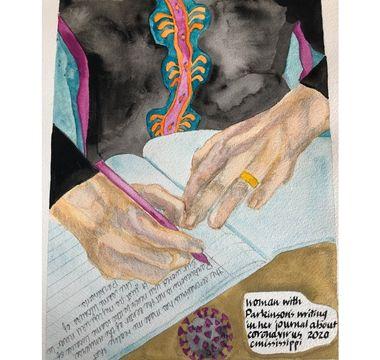

Parkinson’s disease (PD) changes the brain, which can impact the whole body. While slowed movement and stiffness are among the more familiar PD symptoms, Parkinson’s can also affect cognition — the way someone thinks, how they learn, make decisions, approach and solve problems. Though some people notice thinking changes (also called cognitive changes) decades after living with PD, others can begin noticing challenges even prior to a diagnosis.

Cognitive changes can be difficult to discuss. People sometimes fear that others will see or treat them differently if they open up about their thinking issues. Additionally, they may worry about losing their place in the family, livelihood or independence. Though challenging, recognizing and talking about cognitive changes can help you and your care team identify the best therapies and coping strategies to promote your mental well-being.

Our Mental Wellness Series is dedicated to mental health conversations. This article complements our virtual round-table conversation, Addressing Parkinson’s-Related Thinking Changes. This article can help you recognize, treat and cope with cognitive changes related to Parkinson’s:

Recognizing PD-Related Thinking Changes

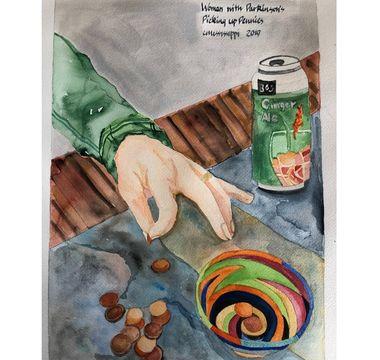

Have you ever said, “don’t talk to me while I’m cooking,” or doing a specific task? While everyone struggles to some degree with multitasking, it is particularly difficult for people with Parkinson’s. Other tasks that rely on executive function, such as participating in group conversations, reading a book or balancing a checkbook, can also be challenging.

Executive function is an umbrella term used to cover many cognitive skills that impact daily living. These skills include attention, focus and multitasking, as well as those involved in problem solving, planning and following multi-step instructions. These abilities help us accomplish everyday tasks and make important life decisions. Parkinson’s can also impact other cognitive areas, such as thinking speed, word-finding, language and speech, vision, depth perception and more.

Addressing Cognitive Symptoms

Since Parkinson’s disease affects cognition, it can be hard to know whether memory and thinking changes are PD-related or due to normal aging, medication, stress, sleep issues, depression, anxiety or other health conditions. If you or a loved one suspect memory or thinking changes, talk to your neurologist. Sometimes, adjusting PD medications can help. Other times, effectively treating other symptoms and conditions can improve thinking issues.

Exercise is a powerful tool to improve not only PD movement symptoms, but some non-movement symptoms such as changes in memory and thinking. Research shows that exercising regularly can improve concentration, information processing and overall cognition. Participating in a Parkinson’s-specific exercise class, going for a walk, taking a yoga or Tai Chi class or stretching can help to improve your cognitive function.

Your neurologist might also refer you to other specialists, such as neuropsychologist or speech-language pathologist. These healthcare professionals offer specialized assessments and teach strategies to cope with thinking changes and improve daily living.

Self-care and support are important to a care partner's well-being at every stage of Parkinson’s. When a loved one is experiencing significant cognitive changes there is an increased risk of caregiver burnout.

Prioritizing Mental Wellness Throughout Cognitive Change

Self-care, creative strategies and staying social can help you maintain your mental well-being while coping with thinking changes. These tips can help:

- Give yourself permission to feel grief. Our thoughts, memories and the way we think form part of our identities. Experiencing cognitive change can cause feelings of loss. Recognize and honor your feelings around these changes.

- Lighten your load. Accept help — whether with medication management, making your home safer or transportation. Even though it can be difficult, accepting help allows you to focus on other important tasks and activities.

- Lessen your stress. Research suggests stress can worsen movement and non-movement PD symptoms, including executive function and cognition. Exercise and mindfulness, the practice of being fully in the present moment, decrease stress and are linked to symptom improvement.

- Use strategies to compensate. Sticking to a daily routine and limiting distractions can make it easier to remember the essentials. Reminders on your smartphone or on a piece of paper in the right location can also provide useful cues to keep you on track. Other strategies include gathering all items needed for a task — preparing a recipe, for example — and putting them away as you go.

- Stay engaged. Building healthy social connections can help keep cognition strong. Foster relationships with friends, family and members of your community. Consider finding a new support group to share your experience and connect with others. Call our Helpline 1-800-4PD-INFO (1-800-473-4636) to find a nearby group or visit PD Conversations, our online community.

Advanced Thinking Changes

As Parkinson’s advances, thinking changes can evolve from subtle changes to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or even dementia — more severe thinking changes that can impact independence. Talk to your doctor about how to best manage advanced thinking changes.

Research shows some medications used in Alzheimer’s disease may have benefits in Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), including donepezil, galantamine and the FDA-approved PDD medication, rivastigmine.

Helpful Resources

The Parkinson’s Foundation is here for you. Explore more of our mental wellness resources now:

Learn More

Explore all of the topics in our PD Health @ Home Mental Wellness Series.

Related Blog Posts

Start 2026 Strong: Simple Resolutions for Better Health