Summer Podcast Playlist: Our Top 7 Podcast Episodes to Get you Through the Season

Whether you’re planning your next beach escape or gearing up for a road trip, the need for entertainment is key, and what better way to tune out than tuning into our podcast?

Featuring the latest treatments and techniques in the Parkinson’s disease (PD) field, our Substantial Matters: Life and Science of Parkinson’s podcast features the experts in the Parkinson’s community who cover a series of PD topics including employee dynamics, the benefits of exercise, alleviating voice challenges and more!

We’ve made it easy for you by picking out our top recommended podcast episodes for the summer― think of this as your curated PD podcast playlist. Just a click away, these episodes will transport you into the labs, offices and meeting spaces of PD health professionals who are eager to share more about your PD topic of interest.

The benefits of music therapy for Parkinson’s have been well established. Rhythm and rhythmic cuing can help with initiation, coordination and maintenance of movement. Benefits can extend to cognitive functions, communications abilities and mood. Some music therapists have furthered their education as academically trained professionals specifically in working with people with Parkinson’s.

Parenting has its challenges and surprises under the best of circumstances, but when a parent has Parkinson’s, it can put added stresses on the family. As parents’ abilities and roles change, children should understand the disease, how it may change their routines and the potential need to take on additional responsibilities.

Parkinson’s is more than a movement disorder. While movement symptoms may be a prominent outward symptom of PD, mood and other emotional changes are also common ― and not just for the person with PD. Care partners may also experience these changes. Often, the best way to recognize these problems and figure out coping strategies may involve other health professionals.

Many people with Parkinson’s want to continue to work. Sometimes all it takes is recognition of their condition by their employer and accommodations to compensate for disabilities. In fact, the Americans with Disabilities Act provides certain protections in the workplace for people with disabilities once they reveal their situation to their employers, who are then required to make reasonable accommodations to do the job.

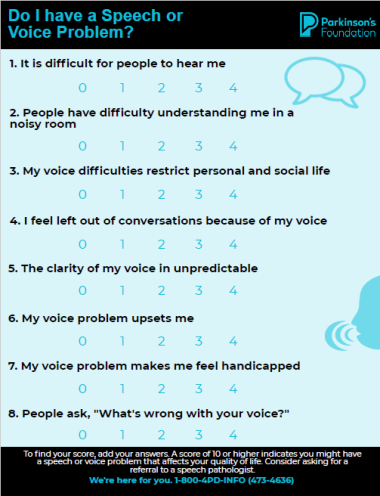

Just as Parkinson’s affects movement, it can affect muscles of the face, mouth and throat, leading to problems with speech and swallowing. People with PD may experience voice problems during the course of their disease. The problems tend to increase as the disease progresses but may occur at any stage.

People with Parkinson’s need their medications on time, every time. Getting them too soon or too late can cause problems. So when a person with PD enters the hospital, which happens 50 percent more often than their peers, the staff often needs to be educated on the importance of delivering medications at the right dose and at the right times ― times that may differ from the usual times that medications are dispensed.

Given the differences women may encounter when dealing with their Parkinson’s, the Parkinson’s Foundation is leading the first national effort to address gender disparities in Parkinson’s research and care as part of an overall Women and PD Initiative. The Foundation has developed new patient-centered recommendations to improve the health of women living with PD.

If you like what you hear, be sure to subscribe, rate and review the series on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. We want to hear what you think about our podcast! Share your feedback here.

Related Blog Posts

20 Parkinson’s-Friendly Gifts

8 Tips for Traveling with Parkinson’s