Coping with COVID-19: Survey Results from People with Parkinson’s During the Pandemic

During the time of COVID-19 are people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) frequently experiencing anxiety? Are they using telehealth services to see their medical team? Are they exercising less or more often than before the pandemic? A Parkinson’s Foundation survey sought to answer these questions and more.

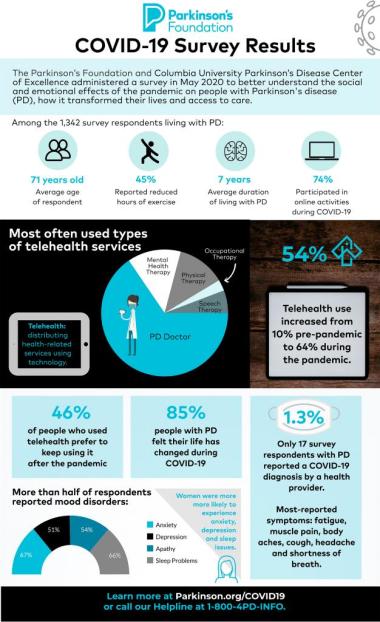

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, little is known about its impact on the health and day-to-day activities of people with Parkinson’s. The Parkinson’s Foundation and Columbia University Parkinson’s Disease Center of Excellence administered a survey to people with Parkinson’s to provide guidance to clinicians, policy makers and the PD community on how COVID-19 has transformed the lives of people with Parkinson’s and their access to care.

“People with Parkinson’s encounter numerous difficulties during normal times, especially when it comes to receiving proper PD medications when admitted to hospitals,” said Phil Gee, Parkinson's Foundation People with Parkinson’s Advisory Council Member. “I am grateful that the Parkinson’s Foundation initiated this COVID-19 survey to capture how people with Parkinson’s disease are coping during this pandemic.”

What did the survey measure?

This survey was administered between May 2020 and June 2020, receiving 1,342 completed responses from people with PD.

The survey asked people with PD about their:

- COVID-19 health status

- Emotional health

- Attitudes and practices related to changes in their routine since the pandemic began

- Telehealth use and satisfaction

Results

Almost all survey respondents came from within the U.S. Respondents live across states that experienced all levels of COVID-19 infection. The average age for respondents was 71, and the average time they have lived with Parkinson’s was seven years.

Diagnosed with COVID-19 and Parkinson’s

Only 17 (1.3%) survey respondents with PD reported a COVID-19 diagnosis by a health provider, five of which had a test to confirm the diagnosis. Within this small group, the most reported COVID-19 symptoms included: fatigue (71%), muscle pain (59%), body aches (59%), cough (63%), headache (47%) and shortness of breath (47%). COVID-19 symptoms lasted an average of 13.5 days.

Mood

More than half of respondents experienced nervousness or anxiety (67%), feeling down or depressed (51%), reduced interest or pleasure in doing things (54%) or sleep disturbances (66%) in the six weeks prior to the survey. Women were more likely to experience these symptoms than men, with the exception of experiencing a reduced interest or pleasure in doing things.

Respondents who reported experiencing frequent mood disruptions (anxiety, worry, depression, reduced interest, sleep disturbances or isolation) during the pandemic where asked to explain why.

- Anxiety was most often attributed to the fear of respondents getting infected (22%) and not knowing when COVID-19 would be resolved (13%).

- Depression was most often attributed to the inability to see or have physical contact with family and friends (16%) and having a history a depression unrelated to COVID-19 (12%).

- Loss of interest was most often attributed to not leaving the house (14%), having lost interest and apathy prior to COVID-19 (14%) and hopelessness or negative feelings about the future (13%).

- Sleep problems were attributed to problems not related to COVID-19 (36%) or worry related to COVID-19 (34%).

Physical and Social Activities

Most people with PD (85%) felt that their personal life had changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly half of people with Parkinson’s noticed some negative change in their Parkinson’s symptoms during the pandemic, but most people with PD said they had no negative change in their relationship with members of their household (65%) or the frequency of their communication with others (75%).

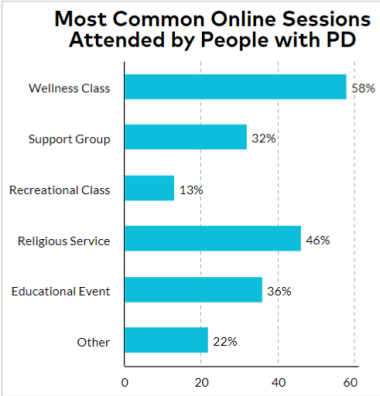

Almost half of People with Parkinson’s (45%) reported reduced hours of exercise, and 73% reported a reduction in activities outside of their home. However, most respondents reported that activities were available online (82%), among whom 92% participated. The most common virtual sessions attended included exercise/wellness class (58%), support groups (32%), recreational classes (13%, religious services (46%), educational events (36%) and other (22%).

As a response to COVID-19, to help ease the challenges of physical distancing, the Parkinson’s Foundation launched PD Health @ Home ― an interactive series of virtual events designed for the Parkinson’s community. To date, more than 230,800 participants have participated in the virtual programming. Currently, PD Health hosts innovative weekly expert-led educational webinars, guided mindfulness sessions and tailored fitness videos. See all upcoming PD Health @ Home events.

Telehealth

This survey measured the use of telehealth services for people with PD during COVID-19. Telehealth use increased from 10% prior to the pandemic to 64% during the pandemic. Those with higher income and higher education were associated with telehealth use.

People used telehealth most often for a doctor’s appointment compared to other health therapies (mental health, physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech and language pathology). Among those who had utilized services, almost half (46%) preferred to continue using telehealth always or sometimes after the coronavirus outbreak had ended. However, having received support or instruction for telehealth and having a care partner, friend, or family member help with the telehealth visit increased the likelihood of using telehealth after the pandemic ended.

Key Takeaways

While better understanding the COVID-19 experiences of people with PD, looking at the bigger picture, survey results suggest several urgent unmet community needs.

Telemedicine or telehealth: the distribution of health-related services and information using technology. Prepare for your next telemedicine appointment with this blog article.

The most notable shift within the PD community is the widespread use of telehealth. Telehealth use significantly increased 54% during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, results made it clear that the PD community urgently needs the expansion of telehealth services to include additional physical, occupational psychological and speech therapies, along with more support for how to use telehealth services and better reaching underserved (low income) populations.

New strategies must be developed to make telemedicine more available to all prospective users. The COVID-19 pandemic has differentially impacted people from lower socioeconomic status and extending telemedicine services to economically disadvantaged populations may help reduce disparities.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were prevalent in people with PD during the pandemic. Household income and employment status were found to be important factors in predicting mood disturbances. Our data strongly suggest disparities across socioeconomic status in people with PD during the COVID-19 pandemic, with those of lower income far more affected by financial and employment uncertainties. Interestingly, factors such as location and local COVID-19 rates were not associated with mood symptoms. This suggests that communities deemed at lower risk of spread are not immune from the overwhelming influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on everyday life.

We must further explore the relationship between PD and COVID-19. Given the uncertainty of how long the hardship of COVID-19 and social distancing requirements may persist, we must identify ways to help the PD community throughout this period. Gathering accurate data on COVID-19 risk among people with PD and improving telemedicine by providing a wider range of services and making it more accessible is essential.

Learn More

- Parkinson.org/COVID19

- COVID-19 FAQs

- PD Hospitalization and Coronavirus Preparedness Fact Sheet

- Centers for Disease Control: Coronavirus

Learn more about Parkinson’s and COVID-19 at Parkinson.org/COVID19 or by calling our Helpline at 1-800-4PD-INFO.

Related Blog Posts

Celebrating 12 Milestones that Defined 2025

Meet a Researcher Working to Make Adaptive DBS More Effective