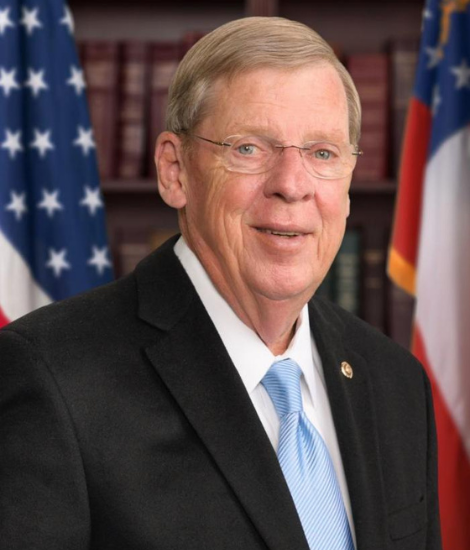

Senator Johnny Isakson passed away in December 2021. The Parkinson's Foundation is grateful for his commitment to the organization and his contributions to make life better for people with Parkinson’s and their families.

Former Senator Johnny Isakson (R-GA) lived by the motto that there are only two kinds of people in the world: friends and future friends.

The Parkinson’s Foundation is grateful to have counted him as a friend.

Senator Isakson, who lived with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and retired in 2019 after 45 years of public service, recently increased his longtime commitment to championing research toward a cure through a leadership gift to the Reach Further campaign. This new, four-year fundraising initiative will raise an additional $30 million to accelerate Parkinson’s research and increase access to healthcare and quality-of-life programs, and $20 million is earmarked to accelerate new Parkinson’s treatments and investigate early-stage drug discovery and development.

“You can’t beat what you can’t understand, but you can beat anything you understand and commit yourself to,” said Senator Isakson. “The Parkinson’s Foundation is taking aggressive steps towards a future without Parkinson’s disease through the Reach Further campaign, and I am proud to support these ambitious plans.”

In his 2019 Senate resignation letter, Senator Isakson described his time in office as “the honor and privilege of a lifetime.” Senator Isakson was disappointed to have to leave the Senate in the middle of his third term because of Parkinson’s complications, but he is seeking to make the best of a challenging situation by devoting his full attention to leading the charge in the fight for a cure.

Senator Isakson, a long-time supporter of the Foundation and instrumental in the success of its 2017 Power Over Parkinson’s Atlanta Gala, joined the Parkinson’s Foundation Board of Directors in 2020. Of his Board appointment, the Senator said, “Having the opportunity to work on neurocognitive research as a U.S. Senator and advocate for Parkinson’s disease was a humbling task. Now, with the opportunity to serve on the Parkinson’s Foundation Board of Directors, it is my hope and sincere desire to share my experience and raise awareness.”

Also in 2020, Senator Isakson established The Isakson Initiative, an organization dedicated to raising awareness and funding for research related to neurocognitive diseases including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and related dementia. Most recently, he helped to create The Isakson Chair and GRA Eminent Scholar position at the University of Georgia (UGA), which raised $4.5 million to attract a leading authority to UGA to focus on Parkinson’s research.

“Upon my retirement, I have rededicated my life to serving the people of Georgia and the United States by doing everything within my power to help those who are working toward a cure for Parkinson’s and other related neurocognitive issues,” said Senator Isakson. “If our great nation continues to invest in public/private partnerships around biomedical research, we can improve and save the lives of millions of people. Through relentless determination, I am confident in our ability to find a cure.”

After more than three decades in the real estate business, Senator Isakson became the only elected official in Georgia to serve in the Georgia House, the Georgia Senate, the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate. He was the only U.S. Senator to serve as chairman of two Senate committees simultaneously — Veterans Affairs and Ethics. He additionally served on the HELP (Health, Education, Pension, and Labor) and Foreign Relations committees. Throughout his expansive career, Senator Isakson was praised for working across political party lines to educate his colleagues about Parkinson’s disease.

As Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, Senator Isakson focused on ensuring that all veterans, including those living with Parkinson's, have access to quality care and the support that they need. He also served as the co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on Parkinson’s Disease. Senator Isakson strongly supported increased research funding at the National Institutes of Health and supported funding Parkinson’s research at the Department of Defense.

Notably, Senator Isakson supported the National Neurological Conditions Surveillance System at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has focused initially on estimating the prevalence and mortality of Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis (MS).

“Senator Isakson is a passionate, relentless advocate for the entire PD community,” said John L. Lehr, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Parkinson’s Foundation. “The Foundation is extremely grateful to have his voice, his expertise and his dedication as a Board member and early supporter of the Reach Further campaign. With the enthusiasm of supporters like Senator Isakson, we will drive research toward new, superior therapies for people with Parkinson’s.”

Through the generous support of leaders like Senator Isakson, the Parkinson’s Foundation will Reach Further to fund scientists at top institutions throughout the world who are working on research designed to advance the understanding and origin of Parkinson’s disease and to propel modern science forward. Funds will also be invested in the Foundation’s flagship initiative, PD GENEration: Mapping the Future of Parkinson’s disease, which aims to provide no-cost genetic testing and counseling to 15,000 people with Parkinson’s. Findings from this study will revolutionize the understanding of the underlying causes of PD.

The Parkinson’s Foundation is immensely grateful for Senator Isakson’s dedication to the Parkinson’s community and his advocacy efforts in helping make life better for people with Parkinson’s. His positive outlook on Parkinson’s and his drive to serve our nation will forever inspire us.

Help Us Reach Further. Donate and check our campaign progress at Parkinson.org/Reach or call us at 1-800-4PD-INFO (473-4636).