Parkinson’s Foundation Hosts First Parkinson’s Symposium in Puerto Rico

Claudia Martinez, MD, Hispanic Outreach Coordinator at the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix, AZ, a Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, did not hesitate when she was asked to join the planning committee for the first Parkinson’s Foundation conference held in the Caribbean. She knew how important this conference would be for the community and what a massive impact it would have on those living with Parkinson’s on the island.

The goal of the conference was to listen to and understand the needs of the Puerto Rico Parkinson’s disease (PD) community and provide information and resources to help people live better lives. The event also sought to establish a network for people with PD and local organizations that provide support.

The committee’s first action was to contact PD organizations and leaders in Puerto Rico. They would need to find speakers who were Spanish-speaking health professionals who understood the challenges faced by everyone in the PD community.

Weeks before the conference was to take place, Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico. All 3.3 million people on the island were affected. The Foundation quickly accounted for committee members and their families who lived in Puerto Rico, but many of them had lost their homes and left the country while infrastructure was being rebuilt.

While the island recovered from the category 4 hurricane, the conference committee moved ahead, choosing a new date and revising their plan. “We knew this would be a big challenge,” Dr. Martinez said. “We decided to continue because now more than never Puerto Rico needed us.”

“When we arrived in Puerto Rico on April 28, we saw the PD community’s enormous needs firsthand. It was amazing to see how people came together, and regardless of the situations they had at home, did their best to attend the conference,” said Clarissa Martinez-Rubio, PhD, co-organizer and Parkinson’s Foundation’s Director of Research and Centers Programs, who was born and raised on the island.

As caregivers, people with PD and healthcare specialists arrived at the conference room, they were welcomed by Foundation staff and a goody bag full of books and resources. Everyone was eager to participate and ready to learn.

All 250 participants grew silent as the first speakers took the stage. Ramon Rodriguez, MD, born in Puerto Rico and now working at UCF Health, and Angel Viñuela, MD, from Dorado, Puerto Rico, are two neurology specialists with a PD focus. They explained the different stages of PD.

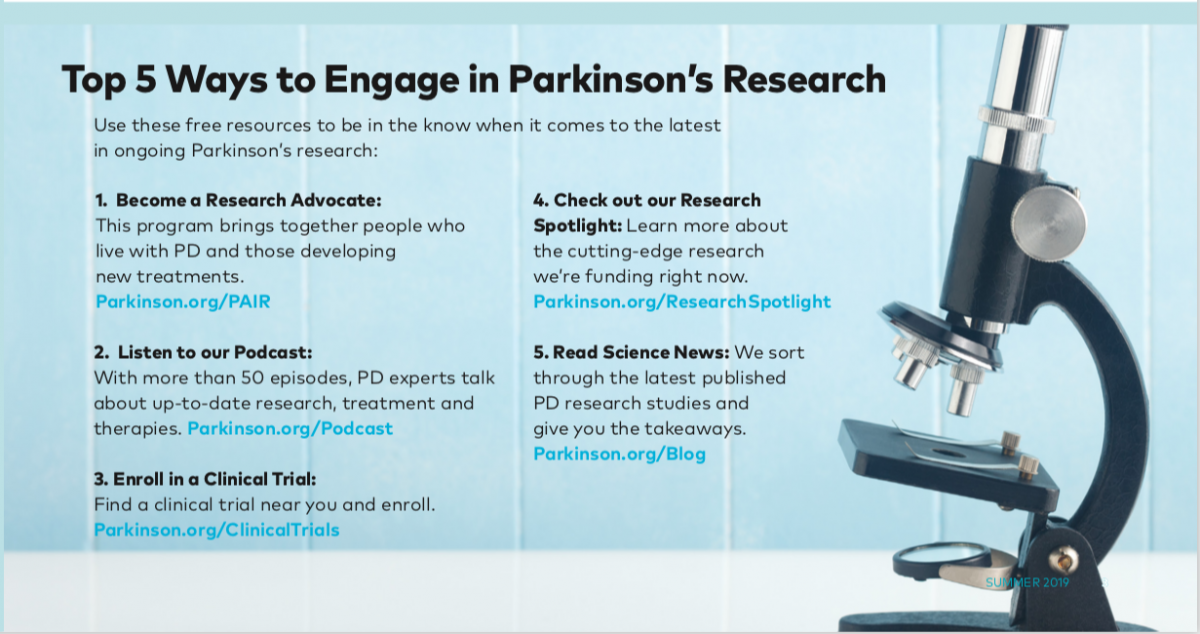

Dr. Martinez-Rubio then spoke about the bilingual resources and services the Parkinson’s Foundation provides, such as the Helpline, Aware in Care kit, educational books and website. She also highlighted the importance of patients being active participants and advocates in their own care and within their community.

Over lunch, patients and family members enjoyed a concert while health professionals underwent a training session led by Fernando Cubillos, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation director of research programs, on neurogenic orthostatic hypotension.

Next, physical therapist Betsaida Cruz, PT, and language therapist Leslie Ledee spoke about the role of exercise and the positive impact of therapies on people with Parkinson’s. They guided the crowd through a series of exercises to help them get a better understanding of speech therapy.

Keynote speaker Alfredo Ruiz, who is living with PD, closed the symposium. Alfredo rode his stationary bike throughout his speech, sharing his powerful story of personal growth. Alfredo not only motivated the audience, but helped them see the connection between passion, persistence and empowerment.

“This is a remarkable effort and we are thankful for that,” conference participant Aura Jimenez said.

Dr. Martinez-Rubio made it a point to speak to multiple people with PD, caregivers and health professionals. “Everyone approached me with gratitude; they were immensely thankful because they felt we gave them hope,” Claudia said. “The energy in the room was powerful. I was able to feel how people were empowered and motivated to continue working for their health and their quality of life.”

Dr. Martinez-Rubio made it a point to speak to multiple people with PD, caregivers and health professionals. “Everyone approached me with gratitude; they were immensely thankful because they felt we gave them hope,” Claudia said. “The energy in the room was powerful. I was able to feel how people were empowered and motivated to continue working for their health and their quality of life.”

Iris Ortiz was thrilled to be given the opportunity to attend. “Thank you for guiding us and giving us information about Parkinson’s and for dedicating your time to create educational activities like this conference to help improve quality of life for us,” Iris said.

“I participated in every activity and they were all a complete success,” said attendee Didi Alice Fatmagul. “I hope to see you all soon.”

The conference was made possible by support from Lundbeck and Abbvie.

Related Blog Posts

10 Tips for Playing Pickleball to Stay Active with Parkinson’s