Mapping the Brain in High Resolution: How the University of Michigan is Advancing Parkinson’s Neuroscience

🧠 What will you learn in this article?

This article explains how researchers at the University of Michigan investigated connections between an area of the brain and Parkinson’s disease. It discusses:

- What the thalamus does in the brain, and how it might impact PD.

- How researchers used PET imaging to visualize neurons in people with PD.

- The impact that Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center funding has on advancing scientific progress toward a cure for PD.

In a landmark investment to accelerate the path to a Parkinson’s disease (PD) cure, in 2019, the Parkinson’s Foundation awarded $8 million to establish four elite Parkinson’s Foundation Research Centers: Yale School of Medicine, University of Michigan, University of Florida, and Columbia University. Each one received $2 million over four years.

In this series of articles, we will share the story of each center — their goals, successes, surprises and the future of their PD research. In this article, we check in with the Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center at the University of Michigan.

The Thalamus and Parkinson’s Disease

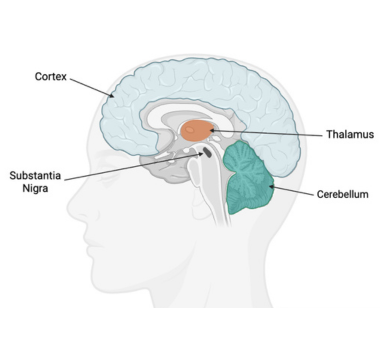

Most research on how Parkinson’s affects the brain has focused on the substantia nigra. This brain region — slightly smaller than a piece of popcorn — plays key roles in regulating movement and healthy cognition.

In PD, the dopamine brain cells in the substantia nigra break down over time, leading to the progressive movement and cognitive symptoms of the disease. However, not all symptoms of PD can be explained by the loss of these substantia nigra neurons. For example, issues with gait and balance or visual dysfunction in PD do not seem to respond to dopamine therapies. This biological puzzle led the Michigan researchers to explore how PD impacts another part of the brain – the thalamus – and how dysfunction in this part of the brain may contribute to PD symptoms, and importantly, how targeting this area for therapies could improve the lives of people living with PD.

The thalamus is made of a pair of small, egg-shaped structures of grey matter that straddle the middle of the brain – one on the right side and one on the left. The most well-understood function of the thalamus is that it acts as a sensory “hub,” relaying signals of sight, sound, touch, and taste from the body to various regions of the cerebral cortex, the wrinkled, outer layer of the brain that provides functions like awareness, memory, and consciousness.

However, recent research on the thalamus has hinted that it may do more than just relay sensory information. In fact, new evidence suggests that the thalamus actively modifies the signals that it sends along, playing an active role in the process connecting sensation to thought and to action.

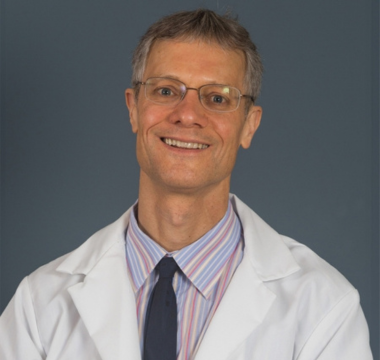

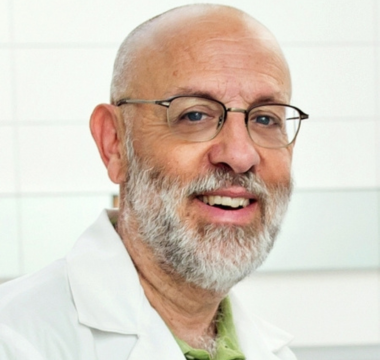

Looking to unravel the role of the thalamus in PD, the researchers at the Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center at the University of Michigan, led by Roger Albin, MD, Nicolaas Bohnen, MD, PhD, and Daniel Leventhal, MD, PhD, each investigated the thalamus in a different way. By taking a cross-sectional approach, this Parkinson’s Foundation funded research team developed a new, thorough and detailed way to look at how thalamic disruption impacts PD — and how to address it.

“The Parkinson's Foundation Research Center was a chance to bring our more basic science researchers into pursuing something in an integrated topic. It was also the chance to explore something that hasn't been explored very much in Parkinson's research — the thalamus — but it's clearly an important area in neuroscience.” Dr. Albin.

Utilizing PET Scanning to Map Dopamine Neurons in the Thalamus

The University of Michigan is home to some of the most advanced brain imaging technologies available, including Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning. Neuroscientists can use this technology to visualize neurons in the brain.

For Dr. Bohnen and Dr. Albin, the Research Center funding combined with PET scanning technology created a rare opportunity to map and measure neurons in the human thalamus. They sought to understand how the thalamus directs vision, balance and movement, and how its disruption could contribute to PD.

Dr. Bohnen focused on how PD affects the dopamine neurons in the thalamus. Early findings from his team found that loss of dopamine neurons in the thalamus was strongly linked to PD-like symptoms and was a better predictor of symptom severity than assessing similar changes in the substantia nigra.

“Thanks to the Parkinson’s Foundation, we have been able to use novel brain imaging tools to study chemical messenger molecules in the thalamic complex in the living brain in people with Parkinson’s and how this relates to more complex gait functions.”

For his Research Center project, Dr. Bohnen designed a larger trial to dive deeper into how thalamic dopamine neuron loss contributes to PD symptoms. He used PET scanning to measure the amount and health of thalamic dopamine neurons in participants in different stages of PD. Understanding how dopamine neuron breakdown in the thalamus coincides with PD movement symptoms could help researchers design new treatments that target this area of the brain.

Exploring the Impacts of Acetylcholine

Another important signaling molecule used in the brain is acetylcholine. Neurons that communicate using acetylcholine are called cholinergic neurons and are the primary focus of Dr. Albin’s research project.

Cholinergic neurons in the thalamus play critical roles in visual attentional functioning - how the mind coordinates what it sees with how it reacts via movement. For example, entering a doorway requires high visual attentional function: arm movement to open the door must be coordinated with moving through the doorway, while also minding any step or threshold that could be tripped on.

“The work of our Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center project cemented our understanding of the importance of another major set of brain systems — the cholinergic systems — that are affected in Parkinson disease.”

Recent studies by Dr. Albin and his team found people with PD that fall more often, a dangerous and common risk of PD, had greater disruption in their thalamic cholinergic neurons. These results hinted that losing such neurons impaired those people’s visual attentional function, increasing their risk of falling.

Dr. Albin wanted to determine whether people with fewer healthy cholinergic neurons in the thalamus had more difficulty with visual attention tasks. Working with Dr. Bohnen, he designed a way to measure thalamic cholinergic neurons using PET scans, coordinated with Dr. Bohnen’s study of dopaminergic neurons.

By comparing PET scan results with participants’ performances on visual attention computer tests, he sought to determine if cholinergic neurons in the thalamus play a role in these tasks. Findings from this research could open new possibilities for future PD treatments addressing movement symptoms that are centered on acetylcholine neurons, in addition to dopaminergic ones.

Impacting Movement Symptoms

While the first two projects studied the thalamus in people, Dr. Leventhal used an animal model, the laboratory rat, to determine how PD-related changes in movement signals from other parts of the brain affect the “motor thalamus”.

The “motor thalamus” is a part of the thalamus responsible for regulating voluntary movement. It receives signals from two key regions of the brain:

-

The basal ganglia: associated with initiating movement

-

The cerebellum: connected to fine-tuning movement

In PD, disruptions in the function of the basal ganglia lead to movement symptoms – but we don’t exactly know how. Dr. Leventhal hypothesized that:

-

Signals from the basal ganglia to the thalamus were more important for reaction time and speed than the signals received from the cerebellum.

-

If he simulated PD-like neurodegeneration in rats, their reaction time would decrease as the signaling from the basal ganglia to the thalamus declined.

Pinpointing where the movement signal coordination occurs in the thalamus could guide new deep-brain stimulation (DBS) targets. Having new thalamic DBS treatment options could make DBS an option for more people with PD, granting them new opportunities to address their movement symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Mining Mountains of Data for Parkinson’s Breakthroughs

As with nearly all clinical research, the COVID-19 pandemic led to delays in Research Center projects. However, the Parkinson’s Foundation supported University of Michigan researchers to wait until it was safe to begin their studies.

“The Parkinson’s Foundation support was essential in maintaining our critical research infrastructure and personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. This allowed us to compete successfully for major extramural funding, including a Udall Center grant and a major grant from the Farmer Family Foundation.” Dr. Albin.

Additionally, the Research Center grant helped Dr. Bohnen and Dr. Albin form an international collaboration with PD researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. These collaborators, led by Teus van Laar, MD, PhD, were coincidentally running a similar clinical study called the Dutch Parkinson Cohort (DUPARC), also performing imaging collection with people with PD in northern Netherlands. By combining the University of Michigan data with DUPARC data, both groups significantly expanded their datasets.

With so much data available, the researchers are still deep in analysis, but some breakthroughs have emerged and have been published in major scientific journals. In particular, the cholinergic research has revealed how acetylcholine neurons across the brain decline over normal aging as well as in PD, charting degeneration patterns that researchers had never fully mapped before. By understanding how these neurons break down both with and without the influence of PD, scientists can better understand how the disease affects or accelerates that process and how to better slow or stop it.

Some early symptomatic correlations with cholinergic neurons have been discovered as well. Dr. Bohnen and Dr. Albin identified specific brain regions —inside and outside the thalamus — that are important for gait and balance. In those regions, when cholinergic neurons were impaired, there were greater issues with posture and movement coordination. These results break ground for new treatments to be developed that target those regions to help with balance and gait symptoms.

Dr. Leventhal’s research into the motor thalamus using rats is still ongoing, with results soon to be reported. In the meantime, his project has inspired collaborations with other researchers at the University of Michigan, investigating other dopamine neuron dynamics in rats with Christian Burgess, PhD, and identifying new brain feedback signals that could guide DBS placement during surgery with Enrico Opri, PhD.

“There is so much exciting research across disciplines right now. I teach a class on PD research to undergraduates and am amazed at how much I have to update the curriculum every year.”

A Research Center Becomes a Launchpad for PD Research

Research projects, especially clinical studies involving complex imaging, require significant time and funding. The Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center designation and its stable and long-term support allowed researchers to embark on this ambitious PD research effort.

The early results from these studies, and the many breakthroughs still to come from the analysis of the collected data, show how critical this support is in driving PD research toward new treatments. Their projects have revealed new insights about how PD affects neurons in the thalamus and the brain overall, guiding future treatment design to improve symptoms.

“We are on the cusp of understanding at a deep computational level how the brain regions affected by PD normally interact with each other, and how that changes in PD. Armed with that understanding, I am hopeful that we can more efficiently restore motor and nonmotor function with fewer side-effects to people with PD.”

University of Michigan researchers have developed a launchpad of PD research that spans not just their institution, but across the world. As their scientific work continues, their findings will propel the university and the greater PD research community toward new treatments and, someday, a cure.

Learn More

The Parkinson’s Foundation works to improve care for people with PD and advance research toward a cure. Learn more with these resources:

-

Read the first article in this series: From Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center to Powerhouse: How Yale Became a Leader in Parkinson’s Science.

-

Discover how we are working to close gaps in knowledge about PD: Advancing Research.

-

Learn about and enroll in PD GENEration — a global genetics study that provides genetic testing and counseling at no cost for people with Parkinson’s.

-

Explore ways to get involved in the Parkinson’s Foundation — from becoming a research advocate to joining a research study.

Related Materials

Related Blog Posts

Meet the Researcher Working to Restore Sleep in Parkinson’s