What's Hot in PD? An Update on DAT Scanning for Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis

In 2011, the FDA approved a diagnostic test for Parkinson’s disease. The DaTscan (Ioflupane I 123 injection, also known as phenyltropane) is a radiopharmaceutical agent which is injected into a patient’s veins in a procedure referred to as SPECT imaging. DaTscan, when it was approved, was considered an important addition to the armamentarium of the bedside clinician. In 2011 I wrote a What’s Hot column on DAT scanning, and this month I will update that posting and bring everyone up to date on the impact of this test.

One of the most frequently asked questions about Parkinson’s disease is whether or not to pursue DaT or PET scan to confirm a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The short answer is that the DaT test is over-used in clinical practice, and is only FDA approved to distinguish potential Parkinson’s disease from essential tremor. In fact, the test only tells the clinician if there is an abnormality in the dopamine transporter, and does not actually diagnose Parkinson’s disease (could be parkinsonism). PET is also overused, though it can be a more powerful diagnostic tool when in the right expert hands.

If you have already received a diagnosis from an expert, and are responding well to dopaminergic therapy, in most cases of Parkinson’s disease, PET and DaT scans would not add any new information, and may prove unnecessary. In cases where the expert is not sure of the diagnosis – is it essential tremor or Parkinson’s, for example-- or where a potentially risky procedure is being considered (e.g. deep brain stimulation surgery), it is reasonable for your doctor to recommend a PETscan or DaTscan. It is important to keep in mind that PET and DaT scans should be performed only by experienced neurologists who have executed a large volume of Parkinson’s disease scans, because experience is important in accurately reading the imaging results. One important update is that DAT scans can and have been misread since the FDA approval in 2011. The reason DAT scans can be misread is because the interpretation is performed entirely by the eye (there are no hard numbers to make the diagnosis). This type of “qualitative” interpretation is subject to error. We always recommend that the interpretation be performed in the context of the clinical symptoms of the patient, and when in doubt to get a second opinion from a Parkinson’s expert.

Here is how the scanning process works for DaT: First, the PD patient receives an injection of the imaging agent. After injection, the compound can be visualized by a special detector called a gamma camera. This scan measures something called the dopamine transporter (DaT), and it can help a doctor determine if patients are suffering from essential tremor vs. Parkinson’s disease or another parkinsonism (i.e., other problems affecting dopamine systems that have symptoms that look like Parkinson’s disease). The side effects if they occur are minimal (e.g. headache, dizziness, increased appetite and creepy crawly feeling under the skin). PET scans and DaT/SPECT scans examine the "function" of the brain, rather than its anatomy (appearance). This is an important point because unlike in strokes and tumors, the brain anatomy of a Parkinson’s disease patient is largely normal. These scans can reveal changes in brain chemistry, such as a decrease in dopamine, which may help identify Parkinson’s disease and other kinds of parkinsonism. There are several compounds available for use in both PET and SPECT scanning; however PET scans typically focus on glucose (sugar) metabolism, and DaT/SPECT scans focus on the activity of the dopamine transporter.

The new DaT scans use a substance that "tags" a part of a neuron in the brain where dopamine attaches to it, thus showing the density of healthy dopamine neurons. Thus, the more of the picture that "lights up", the more surviving brain cells. Dark areas could mean either Parkinson’s disease or parkinsonism.

In Parkinson’s disease, people will lose cells in a part of the brain associated with movement referred to as the basal ganglia. There is a common pattern seen in people with Parkinson’s, with the cell loss starting on just one side, towards the back of the basal ganglia. Over time, the affected area spreads across the entire region. However, as part of the typical aging process, it is normal to lose some of these cells—therefore it takes an expert to read these scans and figure out if the changes are due to normal aging or due to disease. There are typical scan patterns that may emerge. The more widespread the decrease in uptake on the scan, the more advanced the degeneration.

Interpretations of DaT scans can be tricky. The first determination is whether the scan is normal or abnormal. Next, the expert will determine if the scan follows the pattern of Parkinson’s disease or parkinsonism. Finally, a determination will be made as to the severity of the brain cell loss.

PET scans are FDA-approved for the diagnosis of dementia, but not for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. However, if you or your relative has cognitive impairment, the scan can be ordered to examine for the presence of Alzheimer’s changes, as Parkinson’s disease can co-occurs with Alzheimer’s. The cost of a PET scan ranges from $2,500-5,000. Many expert centers perform PET scans for free under research protocols.

Recently, in studies that have attempted to diagnose Parkinson’s early in its course, researchers have found that a subset of patients thought to have Parkinson’s disease have turned up with negative PET or DaT scans. These patients do not seem to develop the progressive symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The findings are humbling, and they lend credence to the importance of following patients over long periods of time to ensure both accurate diagnosis, and also appropriate treatment.

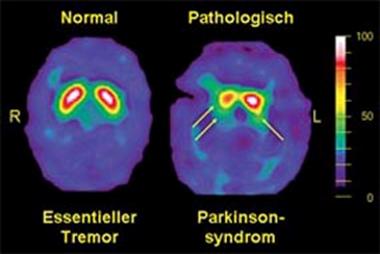

An example DaTscan is shown below and it demonstrates essential tremor on the left (normal DaT), and a parkinsonian syndrome on the right (decreased DaT).

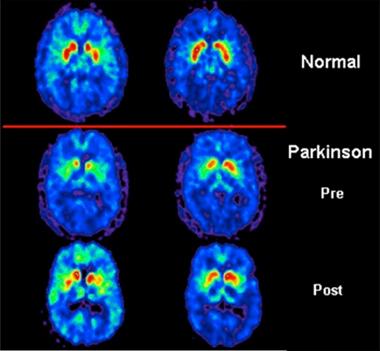

An example of a PET scan is below and it reveals: in the top panel a normal scan, in the middle panel abnormalities in the putamen (red uptake in the figure) in a patient with Parkinson’s disease, and in the lower panel a return to an almost normal scan following the introduction of levodopa.

In conclusion, in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain (e.g. Parkinson’s disease versus essential tremor), a DaT or PET scan can be very useful. Patients and their families need to be aware that in general, these scans cannot reliably separate Parkinson’s disease from parkinsonism (multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclearpalsy), and thus if you seek a scan you will still need an expert to sort out your clinical picture and eventual diagnosis. If you have already been diagnosed, and your symptoms are progressing, and you have an adequate response to medications, a PET or DaTscan will add little new information and therefore will not be necessary. A scan should never replace a clinical examination, and findings should be correlated to the symptoms of an individual patient. Since the interpretation of these scans is often qualitative (by the eye, especially with DaT), a second opinion in uncertain cases can be helpful.

You can find out more about our National Medical Director, Dr. Michael S. Okun, by also visiting the Center of Excellence, University of Florida Health Center for Movement Disorders and Neurorestoration. Dr. Okun is also the author of the Amazon #1 Parkinson's Best Seller 10 Secrets to a Happier Life and 10 Breakthrough Therapies for Parkinson's Disease.

Related Blog Posts

Mapping the Brain in High Resolution: How the University of Michigan is Advancing Parkinson’s Neuroscience

Neuro Talk: Newly Diagnosed