Meet a Researcher Working to Make Adaptive DBS More Effective

🧠 What will you learn in this article?

This article highlights ongoing research aimed at improving the effectiveness of adaptive deep brain stimulation. It discusses:

-

The definition of adaptive DBS (aDBS).

-

Adaptive deep brain stimulation and how it can alleviate Parkinson’s symptoms.

-

Research into whether “entrained-gamma” signals may make adaptive deep brain stimulation more effective than the “beta” signals currently used in the treatment.

-

How this research could improve the lives of people with Parkinson’s.

Over time, Parkinson’s disease (PD) medications can begin to lose their effectiveness. When this happens, deep brain stimulation (DBS) can be a promising treatment option for certain candidates. For DBS, electrodes are implanted into the brain that deliver controlled electrical stimulation that counteracts PD symptoms.

Most DBS systems are designed to deliver consistent stimulation based on settings set and updated by physicians. However, a newer version called adaptive DBS (aDBS), recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use, monitors brain signals associated with PD symptoms in real time and adjusts stimulation automatically. This ability to auto-adjust stimulation has the potential to enhance DBS efficiency and minimize side effects, improving quality of life for those that use it.

Adaptive DBS (aDBS) monitors brain signals associated with Parkinson’s symptoms in real time and automatically adjusts DBS stimulation.

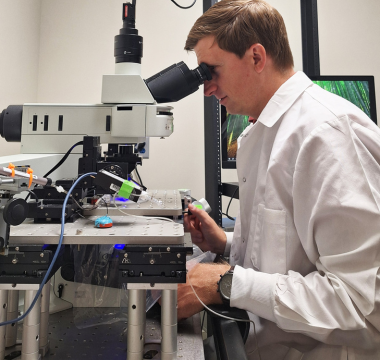

Lauren Hammer, MD, PhD, recipient of a Parkinson’s Foundation Stanley Fahn Junior Faculty Award, is working to make aDBS even more effective by determining which types of brain signals offer the best information on how to adjust stimulation in response to symptoms. Current aDBS technology monitors low-frequency brain waves called “beta” signals, but Dr. Hammer believes that higher frequency “entrained-gamma” signals may be better for predicting and controlling PD symptoms.

“This research aims to advance deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease by identifying the most effective neural signal to guide adaptive DBS,” said Dr. Hammer. “Results could support expanding the set of neural signals used for clinical aDBS, enabling more effective and personalized treatment.”

From her lab at the University of Pennsylvania, a Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Dr. Hammer will first run an in-laboratory assessment where people with PD perform various movement tasks while their brain signals are monitored. This will provide data as to which type of signal — beta or entrained-gamma — offers a more accurate reflection for when PD symptoms like involuntary movements are occurring.

Dr. Hammer will then take a small group of people with DBS for PD and upgrade them to aDBS for an at-home study. After participants are programmed for aDBS stimulation using both beta signals and entrained-gamma signals, they will switch weekly between these settings, recording how well their symptoms are controlled at home.

At the end of the trial, Dr. Hammer and her team will have data to suggest which signal type guided the best aDBS experience for different types of people with PD.

“I’m deeply grateful to the Parkinson's Foundation for investing in early-career scientists and accelerating progress toward better care and a cure.” – Dr. Hammer

“Receiving this Parkinson’s Foundation award is an incredible honor and an important milestone in my journey to improve the lives of people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Hammer. “As a new faculty member starting my own laboratory, this support comes at a critical time — helping me build the foundation for a research program focused on developing next-generation deep brain stimulation therapies. Funding at this early stage is vital to turning promising ideas into impactful treatments, and this award will help bridge the gap between training and long-term research support.”

Meet more Parkinson’s researchers! Explore our My PD Stories featuring PD researchers.

Related Materials

Related Blog Posts

Meet the Researcher Working to Evolve Parkinson’s Therapies Through the Blood-Brain Barrier