What's Hot in PD?: What Are the Disease Modifying Therapies in Trial for Parkinson’s Disease?

We always advise patients to ask their doctor what’s new in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Recently, three leading experts at the Parkinson’s Foundation Center Leadership Conference reviewed the field and updated all attendees on several of the exciting therapies currently being tested by Albert Hung, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH); Irene Richard, MD, University of Rochester Medical Center; and Hubert Fernandez, MD, Cleveland Clinic. In this month’s What’s Hot in PD blog we review their latest therapies.

There are several drugs that have been repurposed and are in clinical trials. The advantage of a repurposed drug is that it is already approved by the U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA). The hope for the four drugs listed below is that they will meaningfully slow disease progression.

- Isradipine (pill) is a calcium channel blocker that was previously approved for the treatment of high blood pressure. The idea behind the use of this drug is to block the entry of calcium into brain cells. Research has revealed tantalizing clues that blocking calcium may prevent brain cell death and lead to positive effects and perhaps even change disease progression.

- Exenatide (injection) is an FDA-approved diabetes drug that promotes insulin release and inhibits glucagon secretion. It is glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonist. There are pre-clinical studies which show potential neuroprotective effects in toxin-based PD models.

- Nilotinib (pill) is a cancer drug used most frequently to treat leukemia. It works as a c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor (blocks an enzyme). It is thought to treat the alpha-synuclein deposition that occurs in the brains of people with Parkinson.

- Inosine (pill) was a previously used drug to improve athletic performance. It is not FDA approved, but there has been great interest in using this drug to address stroke, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s. The idea for its use in Parkinson’s disease is that higher blood levels of uric acid may possibly decrease disease progression and this drug is effective at raising levels. The safety of the drug will be monitored especially for things like gout and kidney stones.

There is great interest in gene targeted and enzyme targeted therapies:

- GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease from the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene is of interest to many investigators. The pharmaceutical company Sanofi has a Phase II trial of a glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor to treat people with Parkinson’s who have the GBA gene (GZ/SAR402671).

- The gene that makes amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) and promotes conversion of brain chemicals (dopamine, serotonin) has been a target for clinical trials. There are positive interim results from an ongoing phase Ib trial and a current open-label trial.

- Ambroxol is an older drug that has been used to treat respiratory disease (decreases mucus). It also increases brain GCase activity. There are trials exploring disease modification and dementia. Allergan has a similar drug LTI-291 that may go into clinical trials soon.

- Denali has a LRRK2 inhibitor for people with the genetic mutation (LRRK2) that causes Parkinson’s. It is called DNL201. There is also a second drug DNL151 that is being tested in the Netherlands.

Finally, there is great interest in vaccine and immunotherapy trials:

- There is a vaccine trial called AFFiRiS that passed its safety testing. It is moving into the next phase to see how it will affect symptoms and disease progression.

- There are two antibody Infusion trials using intravenous injections. The current trials are Biogen (phase 2a) and Roche (phase 2b). The safety data from these trials has been promising, but there are not results of efficacy or disease modification.

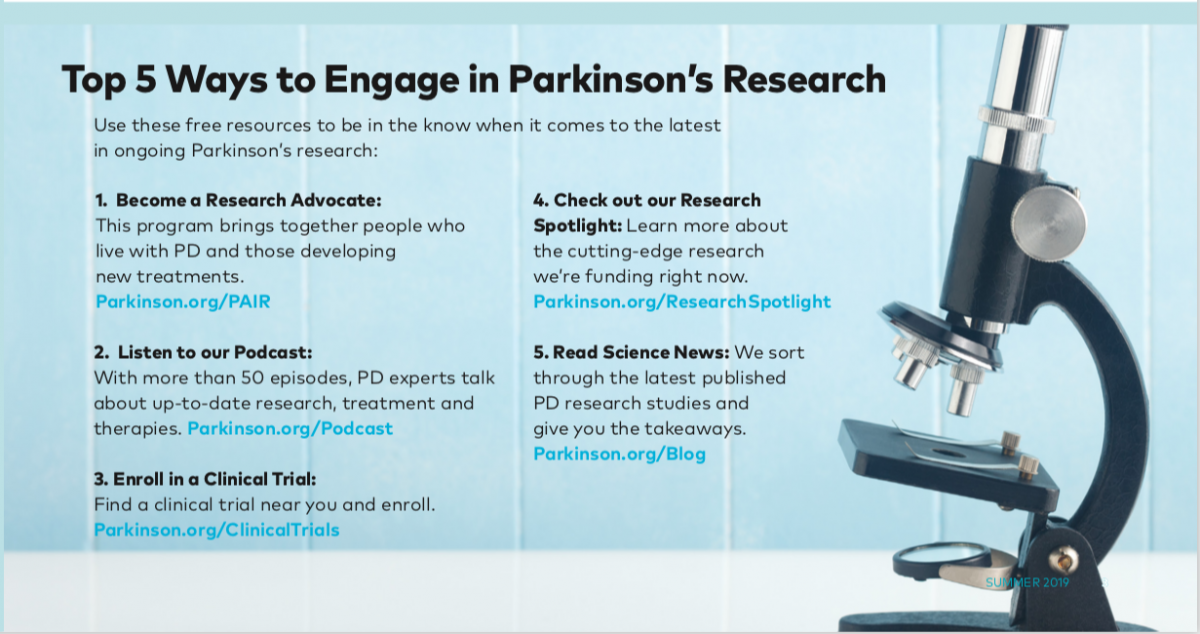

We encourage all people with Parkinson’s to stay abreast of new and emerging therapies. It is important to regularly learn about the latest Parkinson’s treatments and medications, and to check clinicaltrials.gov for the current status of ongoing research. Even if you decide a clinical trial is not for you, you may still find it useful and hopeful to monitor the latest developments in the field.

Learn more about clinical trials at Parkinson.org/ClinicalTrials.

You can find out more about our National Medical Director Dr. Michael S. Okun by visiting the Center of Excellence University of Florida Health Center for Movement Disorders and Neurorestoration. Dr. Okun is also the author of the Amazon #1 Parkinson's Best Seller 10 Secrets to a Happier Life.

Related Blog Posts

Neuro Talk: Newly Diagnosed

Meet a Researcher Working to Make Adaptive DBS More Effective