Health Care Needs of Veterans Living with Parkinson’s Disease

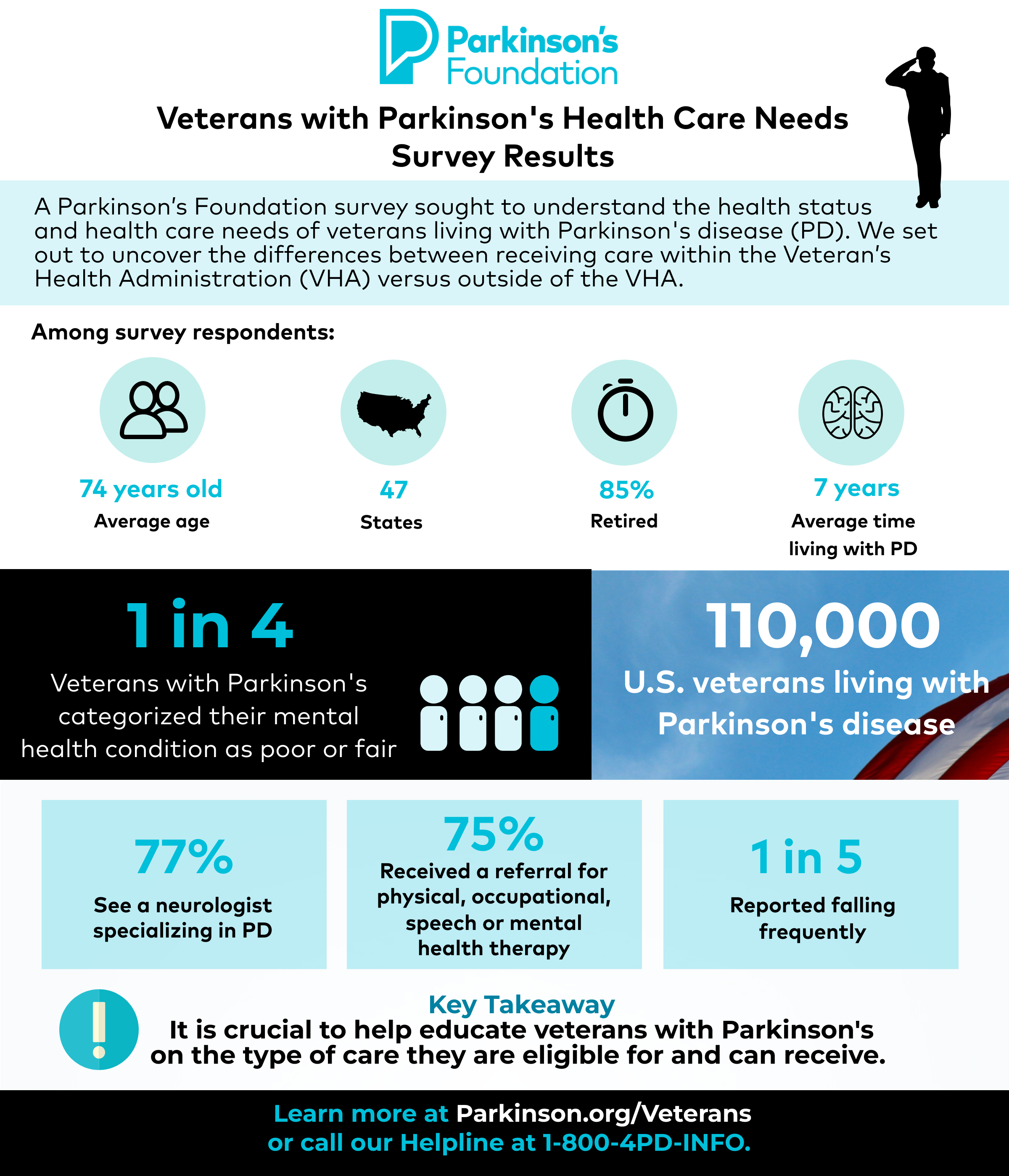

There are more than 110,000 veterans living with Parkinson’s disease (PD). The Parkinson’s Foundation is interested in the differences between those who receive care at the Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA), a government organization within the Veteran’s Administration (VA) that provides primary and specialized healthcare to veterans of the U.S. military, and the veterans who receive care elsewhere.

A Parkinson’s Foundation survey sought to understand the health status, demographics, and health care utilization of veterans living with PD. The goal was to uncover differences between those who received care within the VHA versus those outside of the VHA.

In the U.S. today, there are more than 19 million veterans, yet less than half of these veterans receive care through the VHA. It is important to find out how care can be improved and in what areas care needs to be improved in order to provide the best possible care for veterans living with PD.

Survey Results

Demographics

The Parkinson’s Foundation distributed the survey to 1,532 veterans living with PD in July 2021 and analyzed 409 complete responses. Survey participant demographics include:

- Responses from 47 states

- Average respondent age was 74 years

- Average amount of time living with PD is 7 years

- Primarily white males with around 94% of respondents being white and 92% being male.

- Respondents were mainly retired (85%)

Health Service Utilization

Only one-fifth of participants reported receiving care from the VHA. Among those who utilized care from the VHA, 23% did not know that the VHA offered specialized care. Among all respondents:

- 77% reported seeing a neurologist specializing in PD

- 75% reported being given a referral for either physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech language pathology or mental health therapy from their PD provider

- Physical therapy was the most common referral (67%)

Mental Health

One in three respondents reported mental health concerns in the previous 12 months. Those receiving care at the VHA were more likely to report mental health concerns and were more likely to report poorer mental health, but were also more likely to talk about their mental health concerns with someone (a doctor, friend, family member, etc.).

Reported Falls

Among all respondents:

- One out of five reported falling frequently

- Two out of five reported having frequent near falls

- One-fifth of those who experienced one or more falls, did not report the fall(s) to anyone.

Key Takeaways

This study illuminated key differences and areas for improvement both inside and outside of the VHA. The results from this survey show that:

- Getting referrals for allied and mental health early is vital for veterans living with PD

- One out of four respondents categorized their mental health condition as poor or fair

- Of those who reported a fall in the survey, only half reported the fall to their health care provider

- Educating veterans with PD on the type of care they can receive and are eligible for, whether that be through the VHA or not, is crucial

- Those receiving care at the VHA were more likely to experience negative health complications but were also more likely to utilize referrals hinting at an underlying difference between those who receive care at the VHA versus elsewhere.

Learn More

The Parkinson’s Foundation believes in empowering the Parkinson’s community through education. Explore the below Parkinson’s Foundation resources for veterans and their loved ones:

Related Blog Posts

7 Resources for Veterans with Parkinson's