My PD Story

Ripley Hotch

In the northwest corner of Alabama, three stones sit in an old graveyard outside the Wesley Methodist Chapel. One is a large, somewhat ostentatious double gravestone with the names of Owen's parents, their birth and death dates. I know those death dates are right because I had them carved.

Beside that stone are two matching granite stones, one bearing Owen's name, birth and death dates, and the other with my name and birth date. He had insisted we get the stones. He had always wanted a Celtic cross on his, but when we went to choose, he settled on the simple small stones. It was a couple of years before he died, and so they have now been there for 10 years.

I like to think it was his last nose-thumbing attempt to say to all those stiff-necked Bible-thumpers that we were here, that we belonged as a family. No more hiding, no ignoring, carved in stone. Still, maybe it's a bit too subtle. I've thought of adding a line to mine: “My husband's to the right.” The way we lived was simply to be who we were as a couple. If you didn’t approve or didn’t like it, too bad. We were an example, I suppose.

I have not been to the cemetery since we buried Owen that cold December day seven years ago. He wanted a funeral, so we had one.

An old girlfriend spoke briefly about how she had carried a torch for him for years. It was funny and sweet. A Baptist minister recommended by the funeral home conducted the service—all platitudes and prayers that Owen generally had no use for. Recorded music. A eulogy that was just the obituary that I had written. No one except his friends I had grown to love knew what to do with me or how to treat me. Was I a widower? A “longtime companion”?

We had 40 years together. I knew what I was—he had seven relationships before me, including an actual marriage to a woman, and I was his last, absolute choice, absolutely loved. How many can say that?

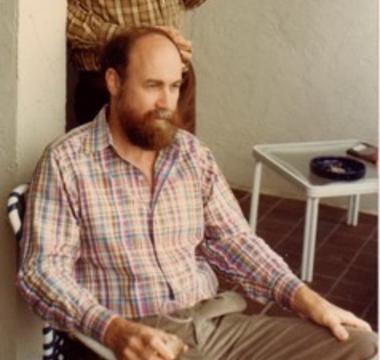

There's a picture of him that I took on our last trip in 2012, two years before he died. It was a loop through France with my brother, Kim, and his wife, Pam. They were a huge help, since Owen was frail, and his body was failing him. I probably should not have taken him, but the way his disease worked, he would often seem just fine. And on that trip he did pretty well.

But that picture captures him in a way that few others really do. That sort of knowing look that had a mischievous angle to it, as if he were thinking of some remark or trick that would catch me by surprise.

There's a section of one of Horace's odes that I've always liked, and even committed to memory once. No room on my stone, for it, though. Not sure my translation really does it justice:

Alas, friend Postumus, the fleeting years slip past, nor will piety, nor wrinkles brought by aging wisdom deter indomitable death.

The Parkinson’s Diagnosis

Our long and winding road eventually brought us to Asheville, NC, where we had two bed and breakfast inns. At the second, one of our guests was a neurologist. She asked me to step outside and asked me if I had noticed that Owen’s right hand was moving in an odd way. I hadn’t really. She advised me to take him to a neurologist to see if he might have Parkinson’s.

We went to see Asheville’s leading neurologist on the disease, and sure enough, that was the beginning of the medications.

Complicating everything, two years after his diagnosis, I had my own diagnosis: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. That meant surgery, chemo, radiation—all while trying to run a business and help Owen with his Parkinson’s.

But we managed. We were lucky for the first few years that he did not have serious physical issues. Outside of the minor tremors, the meds seemed to keep the symptoms under control.

It was only after retirement, when we could take a breath, travel, etc., that things slowly got worse. He began to have balance issues, started being stooped, and simply aged quickly. The last picture I have of him, he just looks old in a way he never had.

One of the things you learn as a caregiver is that it all falls on one person. What I learned slowly, and through the extraordinary and generous help of others, is that you can do it. It’s hard, but it is an act of love. What I learned, and what everyone who survives it learns, is that you need to build and hoard your own strength. You cannot be a caregiver successfully without being a caregiver for yourself.

We dealt pretty well with the physical issues. One of the results of the cancer was lung trouble for me, and I was assigned to a pulmonary rehab facility where Owen was my support person. Exercise is, as we all know, one of the best ways to keep Parkinson’s at bay, so I was grateful that we had this program. He was so charming, he got more attention from the nurses than I did.

His trouble with balance was such that I felt the bathroom needed to be upgraded. It was designed by another gay friend who is a superb architect with real sensitivity to accessibility issues. It is designed to handle a wheelchair if that becomes necessary. It has multiple shower heads, grab bars everywhere, wide sliding doors, and heated floors. I wanted him to have the best.

But one set of symptoms was beyond me. He started having memory problems and worse. He started to see things, to have fears of people breaking into the house, to think that I was someone else, possibly even a thief.

It was, I was fairly sure, the beginnings of some kind of mental issues. I asked our doctor to refer us to MemoryCare, a group a doctors who are focused on helping the family keep their person at home. Our doctor there was the founder, Margaret Noel. Peggy sat me down at the end of our first visit and told me the horrifying truth: Owen was suffering from Lewy Body Disease, the most terrifying of all the dementias.

That began the last part of our journey. We had joined the Asheville Parkinson’s Support Group, and it was comforting to have those around who had understood the earlier part of the disease. But this part, no one had seen. It happens to possibly 10-15 percent of Parkinson’s patients. What happens to the patient is terrible: sleeplessness, delusions, loss of memory, loss of physical control, all kinds of fears. And it is hard on the caregiver, to say the least. He woke me up time and again during the night, so I was sleep-deprived most of the time. At one point I remember losing control in the middle of the night and screaming that if he kept it up I was putting him in a nursing home. I’m not proud of that, but it shows how close to the edge you can get.

I will share only one story. One night, after saying that I wasn’t really me (called capgras syndrome), and insisting I call the sheriff because there was a thief in the house (the other me), he went off to bed. I was so exhausted that I fell asleep in the chair, only to be awakened at 2 in the morning by my neighbor to say that Owen had showed up at his door with a knife, demanding he call the sheriff. My neighbor didn’t panic, and called me.

I went to get Owen, who had managed to get out of the house in 5-degree weather in January, wearing a coat and shoes but no pants.

It was his last year.

I have remained a volunteer with the support group and with MemoryCare. Their support helped me so much, and I hope that I can help others deal with this struggle.

For those struggling as caregivers: There are moments when your guy suddenly is fully "there" unexpectedly. Once, Owen looked up at me and said, "I know what you're trying to do, and I want you to know that I appreciate it." It kept me going every time things got tough. Those are moments you cherish.

The happy ending is that I have a new partner, who had a partner earlier who had the same dementia issues. So we understand one another and life is good.

Related Materials

Freezing and PD

Finding the Right Skilled Nursing Facility

Finding the Right Assisted Living Facility

More Stories

from the Parkinson's community